Artist Peter Greenwood Welcomes Visitors to His Glass Blowing Studio

By Zachary Schwartz

Photos by Ryan Lavine

Artisans have manipulated glass for many centuries. Sources and styles vary, but the same pellucid material has taken the form of ecumenical stained glass windows, Venetian glass decorative objects, and Dale Chihuly’s whimsical sculptures. Today, glass artists continue to experiment with the medium. Peter Greenwood is one such artist.

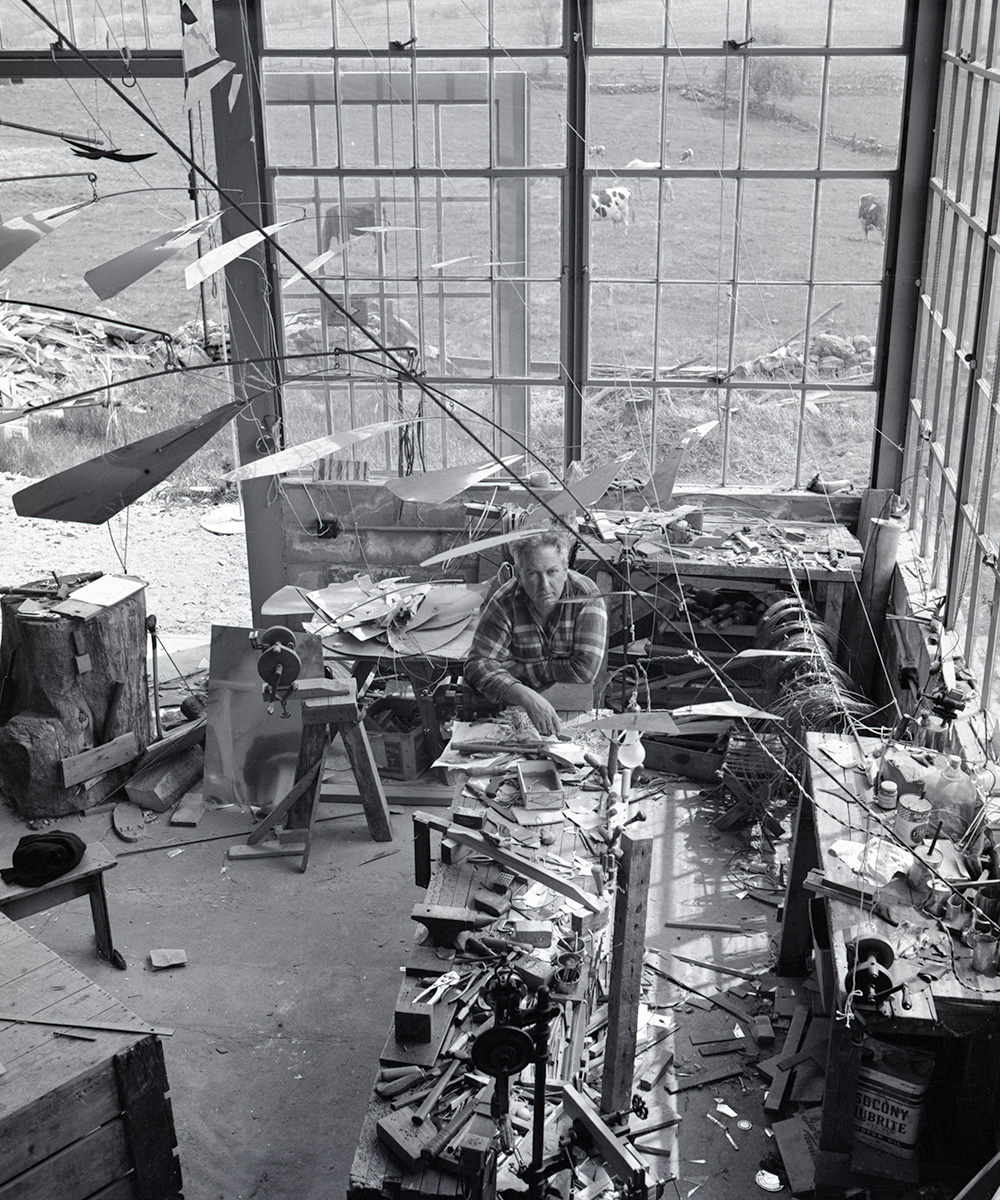

Greenwood took an interest in glass art during late adolescence. “I was attracted to the challenge of working with glass and the spontaneity of working with it,” he says. He left the Rhode Island School of Design to pursue his interest in glass blowing, then landed at the Pilchuck Glass School, where he worked with an Italian master. “It’s a life learning process. I’ve been working with glass for 44 years now, and I’m still learning every time I’m working. It’s all about time at the furnace and experimentation.”

Greenwood’s glass work has manifested through many forms. He has created blown glass vessels, chandeliers, dining room tables, wall sculptures, and more. His work varies in style and technique, from reticello to lace glass to modern freeform. “There’s so much that can be done with glass. You can sculpt it, cast it, make a stained glass piece, and incorporate it in a blown glass piece. There are endless possibilities of working with glass,” says Greenwood.

In search of a large enough space to accommodate a furnace, Greenwood happened upon an unused church in Riverton. The chapel was built in 1829, functioned as a place of worship for well over a century, then changed hands in 1972 to the Hitchcock Chair Company who converted it into a chair museum. Greenwood purchased the building in 2005, renovated it for a year, then opened his art studio and gallery in 2006.

The stone church’s interior is punctuated by stained glass panels and remnant organ pipes. As a glass artist who used to build stone fireplaces, the building was inspirational for Greenwood. He transformed the bottom floor into his glass, metal, and woodworking studio, then built a second floor as an art gallery. Greenwood’s glass artwork is displayed alongside his wife Christine Chaise Greenwood’s paintings.

Greenwood teaches glass blowing courses and creates commissioned installations. Private clients, decorators, and architects have commissioned custom glass furniture and sculptures, including a 2023 installation on view at Connecticut’s Bradley Airport.

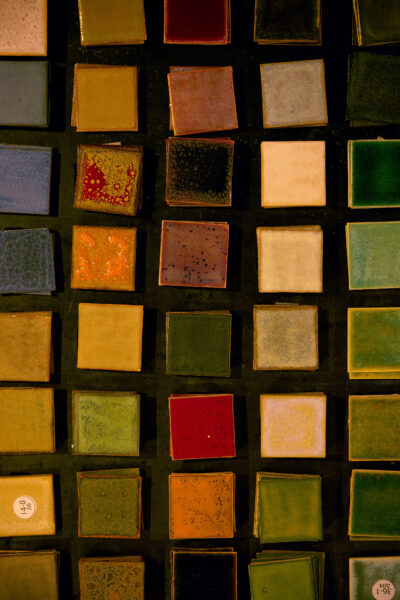

Greenwood welcomes local students of all ages to his chapel-turned-studio for hands-on workshops. “The youngest I’ve had is a five-year-old and the oldest I’ve had is a 95-year-old,” he says. Depending on the workshop, visitors have the option to sculpt a glass paper weight, flower, or blown vase, then tint them with colorful glass beads he sources from New Zealand and Germany.

For creatives interested in experimenting with a new medium, Greenwood is an encouraging teacher. “For people who have any interest in glass and feel like they’re afraid to try it, they have no need to be afraid. People that are shy and intimidated are surprised how easy it is to make a piece.”