June 24, 2022

By Clementina Verge

Lake Waramaug’s crystalline surface reflects not only sunsets and seasonal splendor, but centuries of history shaped by those fortunate enough to have witnessed its beauty.

Connecticut’s second largest natural lake—whose expanse touches Washington, Kent, and Warren—is a “striking microcosm of the American story,” notes Christine Adams, whose family has kept a cottage on the lake for five generations. “It has allowed itself to be reinvented while retaining its character.”

The natural features of this “quintessentially New England” lake formed when the last Ice Age glacier melted have remained unchanged, transcending time and anchoring many cultural and social shifts, from the Indigineous people who first called it home, to Colonial settlers who arrived in the 1680s, followed by decades-long residents, vacationers, and weekenders.

“The Indigenous people are unique in that they have experienced the entire history of this lake first hand,” reflects Adams, who serves on the Lake Waramaug Task Force Board of Directors. “They make up the longest serving stewards of Lake Waramaug,” named after the chief of the Wyantenock tribe that encamped, hunted, and fished here in the summer.

More than ten Native American archeological sites found within two miles of Lake Waramaug emphasize the importance of remembering that the land was “the ancestral home of many who from millenia came before us,” Adams highlights.

A shoreline transformation was underway by the 1730s; Lake Waramaug became an industrial landscape when residents like Daniel Averill and Edward Cosgrove discovered the iron ore on the west shore. The lake began to serve “as a holding pond” for 21 water-powdered industries, including an ironworks grist, sawmill distilleries, and various factories manufacturing everything from tools and furniture, to clothing and grain sacks.

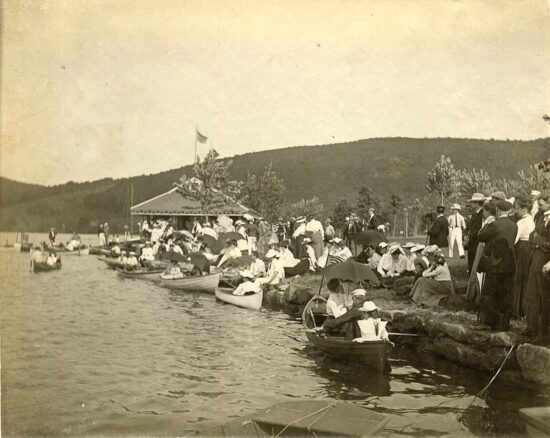

As the Civil War culminated, steam power replaced hydropower, and the community morphed again. The population dropped 20 percent between 1850-1920 as cities attracted workers, but the lake enticed many back, entering “a heyday of sorts, becoming a summer community, an artist haven,” and likely the site of the first campground in America.

“The times were lively,” shares Adams, a researcher at the Gunn Historical Museum.

By the 1920s, 300-400 guests arrived at the Preston train station on Bee Brook Road every summer, traveling Flirtation Avenue in horse-drawn covered wagons while being transported to one of the 17 lakeside inns. Steamboat tours, concerts, and plays at Pavilion Hall, antique car rallies, dances, fireworks, water sports, and regattas became the social norm.

And then, the shoreline transformed again. Some buildings burned between the 1960s and 1980s; others were demolished or sold, making way for today’s waterfront residences.

Lake Waramaug State Park offers public access to swimming, camping, and boating. Beyond those boundaries, the shoreline of the 625-acre lake is privately-owned.

“Although the use of the lake has changed, the inherent sense of place conceived by all that dwell here is constant. Its culture has shifted with every generation, but a unique sense of attachment and belonging is felt by all who know and love Lake Waramaug,” remarks Adams, who speaks from experience.

In the final stages of writing a book, Homespun, she chronicles the history of a centuries-old cottage she recently purchased along East Aspetuck River, whose source is the lake on which her great grandfather built his home, and where her ill father chose to spend his last summer.

“The DNA of this place has interlaced with our own and although each generation has nurtured the lake very differently for more than 10,000 years, its beauty and power to inspire and connect us are constant.”