April 27, 2021

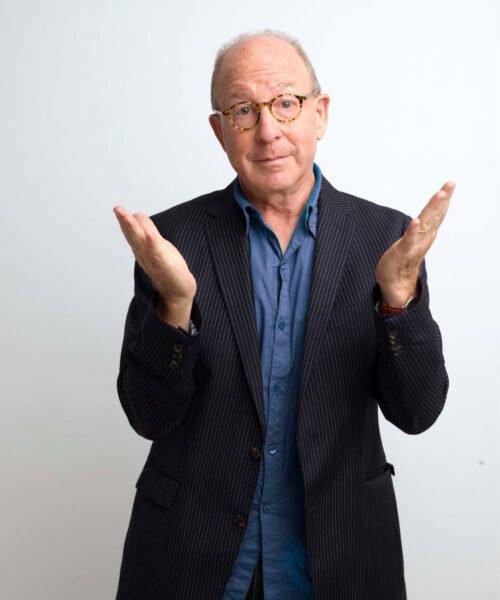

From the Art Critic Jerry Saltz

By Joseph Montebello

Pulitzer Prize-winning art critic Jerry Saltz did not start out wanting to write about art. He dreamed of a career on the other side of the easel—as a real artist.

“It pains me to say it, but I am a failed artist,” Saltz explains. “Pains me because nothing in life has given me the boundless bliss of making art for tens of hours at a stretch in my 20s doing it every day and always thinking about it, looking for a voice to fit my own time.”

But Saltz’s demons kept telling him he wasn’t good enough, that his art was irrelevant, and that he was an impostor. So he caved in and listened.

“Every artist does battle every day with doubts like these,” says Saltz. “I lost the battle. It doomed me. But also made me the critic I am today.”

But before he became a critic, he was a long-distance truck driver. In retrospect Saltz believes it was good for him.

“Everybody begins with or has a certain amount of doubt, and I think doubt is really useful. This is the dark energy that keeps the engine churning. I was a truck driver for ten years. I self-exiled after I stopped making art, and I grew more and more unhappy. I thought, I’ve got to be in the art world. I decided to become an art critic.

“I had no degrees of any kind and I’d never written a word in my life, so I started to read Art Forum, which is kind of the school newspaper of the art world. I would read it religiously and the truth is I never understood a word of it. But I had to learn to write like this, which is the way I first started as a critic.”

In 1998 Saltz was asked to write for The Village Voice.

“My good friend art critic Peter Schjedahl was leaving to go to The New Yorker,” he explains. “It never occurred to either of us that I should consider taking the job.”

Saltz and his wife Roberta Smith, co-chief art critic for The New York Times, were leaving for Italy when The Voice’s editor Vince Aletti called and made him an offer.

“Within ten days I had come to an understanding that if I turned down this job I would be tormented for the rest of my life every time I read The Voice. That pain was greater than the fear I had of writing a weekly column. So I took the job and that’s where I really learned to write. A deadline every seven days will do that for you.”

Since 2007 Saltz has been senior art critic at New York Magazine. He and Smith, who have a home in South Kent, will see 25 to 30 shows a week, in galleries, museums, artists’ spaces, just about any place open to the public with regular hours.

“When the openings are over and people start going to parties and dinners, Roberta and I go back home and start writing. We pretty much discuss art 24/7. When you do something you love and are this passionate about, especially if it’s writing, it means this is what you are.”

Although he is not a practicing artist, Saltz knows more about the subject than most and shares his thoughts in his most recent book How to Be an Artist. It is meant for artists of all kinds. In short, succinct chapters he tenders advice on how to develop your inner artist and to not be afraid. He even suggests dancing—at least once a year.