April 20, 2022

Washington’s Agricultural Legacy

By Clementina Verge

From the days when indigenous people worked Shepaug River Valley, to the arrival of Colonial settlers in the 1730s, to modern microfarms, Washington’s rich agricultural heritage spans centuries; its numerous dairy farms once earned Connecticut a reputation as the “Holstein capital.” Faced with difficulties, many farms closed or relocated west, but remaining ones continue to nourish the community while shaping its future.

“In spite of many challenges that both nature and the economy have put in their way, Washington’s farmers have proven to be persistent, resilient, and innovative for more than 280 years,” reflects Patrick Horan, who comanages Waldingfield Farm with his brother Quincy. “We’ve weathered impediments such as elevation, ruggedness, stony soil, droughts, increased production costs and rent prices, and even bankruptcies.”

Though contemporary farming may not resemble the early homesteads of Judea Parish—as Washington was known—it carries on a rich legacy that once included tobacco, pork, and more than 100 dairy farms. Waldingfield Farm, purchased by Horan’s great-grandfather C.B. Smith at the beginning of last century, was among them.

For decades, milking operations thrived, including at Echo Farm, whose butter was recognized at the 1901 Pan American Exposition in Buffalo, NY. But a 1906 drought dimmed the flourishing landscape, and by 1910, Echo sold its land. Between World War I and World War II, more dairy operations ceased throughout New England. In Washington, they whittled from 118 to roughly 50.

Waldingfield was among them; neighboring farmers worked the land in different capacities for 50 years until Daniel Horan, Smith’s great-grandson, reclaimed it in 1990 as a working family farm dedicated to vegetables; sprawling more than 25 acres, today it is one of the largest certified organic operations in Connecticut.

Similar adaptability saved the tenth-generation Averill Farm, purchased in 1746 from Chief Waramaug’s holdings. Between the 1940s and mid-1960s, about 20-30 cows were milked daily, but increased herds did not equate to increased profits, so the family shifted focus to orchards. It was a wise decision, Horan affirms, given the thousands who ascend the hilltop property every autumn for its apples and pears.

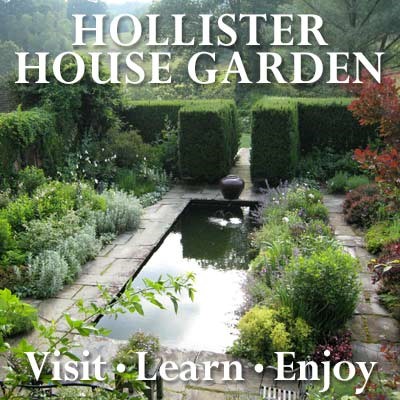

Other farms expanded elsewhere or succumbed to hardships, leaving residual reminders—such as stone walls in the woods—throughout properties that have morphed. The cows at Hollister Farm that grazed the now Hollister House Garden are a faded memory, as is Spicerack Farm once housed on the sprawling Macricostas Preserve.

Significant acreage was sold for housing development, but six-10 working farms remain, Horan says, and all have found innovative ways to create bountiful farmers markets, CSA programs, and engaging community events, such as the farm-to-table dinners.

Agriculture in the area has come full circle, Horan reflects. In the past, local produce was transported into cities—especially after the invention of refrigerated transportation—but since 2020, the Covid-19 pandemic turned many seasonal occupants into year-round residents, increasing local food demand and emphasizing the value of Washington’s rural and agricultural legacy.

“Farms have sustained the community and hopefully the community will continue to sustain them and any new ones established in the future,” Horan notes.