May 7, 2020

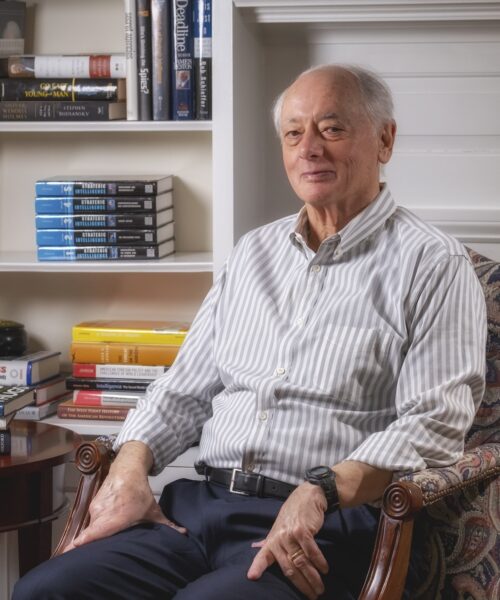

U.S. Intelligence expert lands in Salisbury

By Douglas P. Clement

When a covert agent surfaces in an exotic location in spy movies, trouble isn’t far behind. So when Loch Johnson, a leading expert on U.S. intelligence organizations, moved from his longtime home in Athens, Ga., to Salisbury last June, it meant something.

Over lattes and proper English scones at The White Hart, Johnson anticipates the “why are you here” question. “Grandchildren,” he answers simply. It might be brilliant deep cover—except the story checks out. Johnson’s daughter Kristin Swati, once an analyst for Goldman Sachs, founded the online children’s clothing store Fawn Shoppe in 2010 and lives with her family in Copake, N.Y.

A grandchild attends Indian Mountain School, where Johnson was headed that day to teach first-graders chess, not the topic he lectures on at venues like Georgetown, Yale and West Point—and these days also at Hotchkiss School and Salisbury Public Library.

The Regents Professor Emeritus of Public and International Affairs at the University of Georgia, Johnson is focusing on writing after a four-decade career in academia and holding high level U.S. government positions that afforded him an insider’s view of U.S. intelligence operations. Among his many notable roles, Johnson served as special assistant to the chairman of the Senate Select Committee on Intelligence (1975-76), which investigated intelligence agency abuses, and as special assistant to Chairman Les Aspin of the Aspin-Brown Commission on the Roles and Missions of Intelligence (1995-96).

Johnson’s latest book is “Spy Watching, Intelligence Accountability in the United States” (Oxford University Press), offering an authoritative overview of intelligence agencies and Congressional oversight. His most influential contribution as a book editor is “Intelligence: The Secret World of Spies, An Anthology,” which is so widely used as a textbook for intelligence studies courses it has made The Washington Post’s best-seller list.

“I find my writing time has doubled,” says Johnson of his emeritus status and move to Salisbury. His work in progress about covert actions is entitled “The Third Option.” In supercharged political situations, diplomacy is the first option, going to war second. As a third option, Johnson says, “You try and change the world using hidden forms of intervention, which might ultimately include sabotage and even assassinations.”

It’s a topic with high audience appeal judging by the questions Johnson gets at speaking events. Older guests want to know if there’s a deep state and exactly what the CIA does, and students ask how to get a job at the CIA. “A truly sophisticated audience asks if we really need to conduct these activities,” says Johnson, who generally finds value in the covert operations but thinks judges the scope of intelligence agencies to be too narrow.

“They’re riveted in on military threats,” Johnson says, and should expand the focus to issues like the environment and pandemics. “You go to a security meeting and try to take about ice floes and people snicker. What if you wanted to hide a submarine under an ice floe? There are connections. How long will the ice floe be there? The bottom line is I think the CIA needs to expand its focus.”

Johnson is harsher when it comes to President Donald J. Trump, writing in the January issue of the journal Intelligence and National Security, “No president has engaged in political warfare against the intelligence agencies of the United Sates to the extent Donald J. Trump has, with his three-year-long attack against them.” Johnson, formerly senior editor of the journal, suggests President Trump “could have taken the role of intelligence in national security affairs more seriously, as a lamplight helping the United States to see more clearly the pathway forward in world affairs.”