April 26, 2023

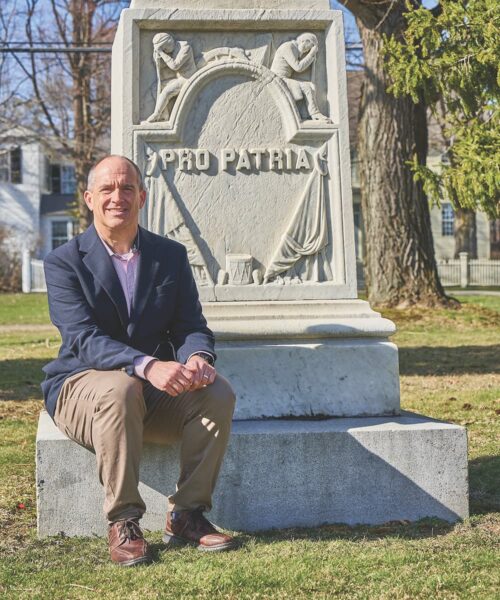

Historian Unearths Surprising ‘Level of Dissent’ in Litchfield County

By Linda Tuccio-Koonz

Peter Vermilyea was burning some energy on a run when a time-worn tombstone caught his eye as he passed the old cemetery on his route. It set him on a new path—a journey toward the days of the Civil War.

“It’s in West Cemetery, the cemetery in Litchfield that I run by almost every day,” he says. “There’s one stone that marks the grave of three brothers; Wadhams is their last name.”

Vermilyea, a historian and author, wanted to learn more about the sibling soldiers. That old tombstone led to new research, now part of an eye-opening book project on how northern communities responded to the war over slavery.

“Those three brothers, all three were killed in a ten-day span, culminating in the battle of Cold Harbor (Virginia),” says Vermilyea, who wanted to know how a community dealt with such tragedy.

“At Cold Harbor there were 141 men from Litchfield County killed in about an hour. That’s the question I started researching: How do you deal with that?”

“I started down that road but got wrapped up in the story of sending them off in the first place.”

Vermilyea, who teaches history at Housatonic Valley Regional High School in Falls Village, and for the University of Connecticut, scoured everything from diaries to newspapers, including the recently digitized Litchfield Enquirer. What he uncovered was surprising, even to him.

“There’s a popular narrative that the northern communities rallied around the flag when the war began, and I was very surprised at the level of dissent that existed in Litchfield County.”

Mobs on the streets made threats against those who opposed the war. There were even armed standoffs.

“There was a farmer in Goshen, whose last name was Palmer, who flew a pro-Confederate flag at his house. People formed a posse, marched to his farm and demanded that the flag be taken down. Some accounts talk about shots being fired.”

Much like today, it was “an incredibly complicated time,” he says, of the war years, 1861-1865.

Vermilyea’s manuscript (he’s in talks with publishers) is unique in its focus—a three-month period from July to September 1862, with equal emphasis on recruits and civilians.

Yes, there were people who wanted to serve and rushed off to enlist, people who opposed the war, and people who enlisted because of the draft, or the money.

But it was more nuanced than that, he says, especially regarding those who enlisted for pay. They weren’t all mercenaries. “Some had fallen on hard times, were providing for families, and could not afford to leave. When the money offered to them to join the army reached a certain point, it became economically viable to act on their patriotism.”

Looking at the big picture, Vermilyea says communities were faced with an unprecedented challenge.

“They had to raise 2,000 men at a time when the war wasn’t going well for the Union and when the realities of war, in terms of death and disease, were on the front page of the paper every week. And they did it. They raised about 2,000 men in a period of about two and a half months, an extraordinary effort.”

About Peter Vermilyea:

His earlier books, Hidden History of Litchfield County and Wicked Litchfield County, were born from his blog, Hidden in Plain Sight. The idea, he says, “is that we can learn so much about our area’s history if we’re willing to become explorers, to kick some leaves aside to see an old foundation, to walk an old road bed, to consider the names of roads, etc… And to a certain extent that is the root of my current project as well, going back to that grave in the cemetery.