By Jamie Marshall

Photos by Joshua Simpson

Student historians share stories of the region’s rich BIPOC past

At a time when the history of our country is systematically being erased, denied, or buried, a group of local high school students are taking a different tact—they are shining a light on it. This past May, 200 middle and high school students from sixteen regional public and private schools gathered at the Troutbeck Resort in Amenia for the third annual Troutbeck Symposium. This student-led forum celebrates and commemorates people of color and other marginalized groups whose contributions to the community have long been forgotten—or simply ignored.

At first glance, the symposium might seem a departure for the resort—whose guests come for its beautifully designed rooms, farm-to-table cuisine, and wellness amenities. Yet, at its core it speaks to Troutbeck’s storied past when former owners Joel and Amy Spingarn were key players in the civil rights movement and the Harlem Renaissance.

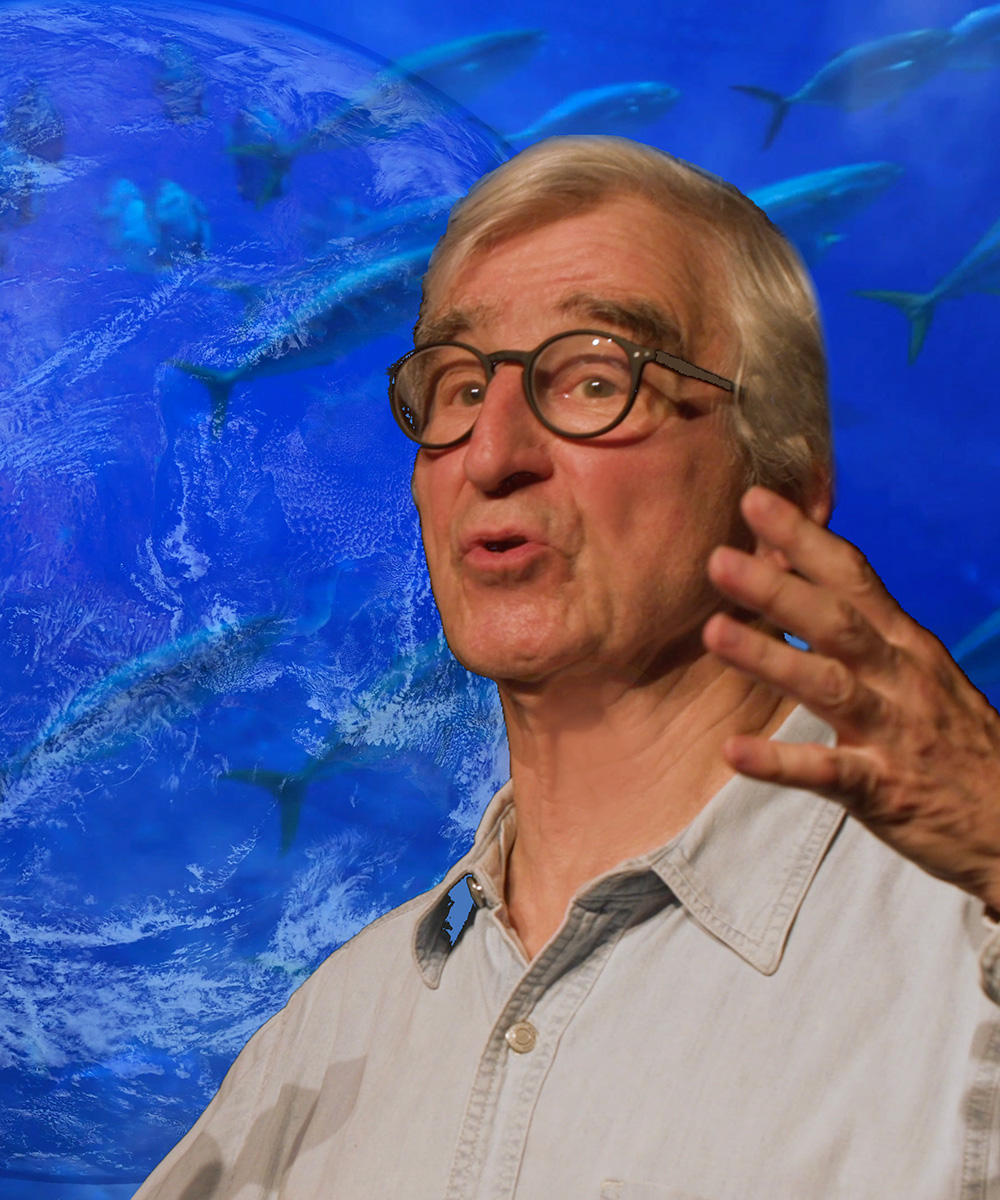

It all started during the COVID-19 lockdown when Salisbury history teacher Rhonan Mokriski challenged his students to find little known stories about African-American history in the area. Mokriski enlisted the help of documentary filmmaker Ben Willis. Among the highlights was a short film called “Coloring Our Past,” featuring Katherine Overton, a passionate historian whose mother was born in Lakeville and who traced the Cesar side of her family back five generations. Because Katherine was riding out the pandemic at her daughter’s home in Frisco, Texas, her two grandsons—Isaac and Kasai—were enlisted as producers The project was so successful that a year later the Troutbeck Symposium was launched.

“From the beginning the idea was to give it to the students and let them run with it,” said Mokriski.

And run with it, they have. This year’s films covered tough topics: modern day lynchings, the silent protest march of 1917, a private school for mentally challenged children, and destruction of the sacred lands of a local Indigenous tribe, to name just a few. For Salisbury School senior Kasai Moore (Overton’s grandson who came to the school as a junior), it was a chance bring his family legacy full circle.

His documentary “Roots” traced his family’s ties to the area back five generations including his great, great grandmother, Matilda Cesar Williams and her brother Arthur who worked at the Troutbeck estate. “It takes my breath away to imagine my uncle Arthur, the family chauffeur, ferrying Langston Hughes or Zoe Neale Hurston from Wassaic train station to the Troutbeck,” he said.

For Moore, the experience was deeply personal. A gifted soccer player, he arrived at Salisbury hoping to fulfill his dream of playing for a college team. An early season-ending injury forced him to pivot and he now plans to pursue a career in cybersecutiry. “It was a difficult transition to come here my junior year but at the same time it felt like a calling for me to do it,” he says. “And then I learned about my family’s connections to the area, and how they weave into the tapestry of the landscape. It made me feel like I was part of something and I can take that feeling with me wherever I go.” —troutbeck.com