August 21, 2020

Furniture Designer Keeps It Small and Local

By Wendy Carlson

For 45 years, Ian Ingersoll has been creating custom cabinetry in the sleepy town of West Cornwall. Up until the pandemic hit, his guild of ten craftsmen were producing pieces for architects and designers of hotels and restaurants throughout the U.S. When COVID-19 forced those businesses to close, Ingersoll shifted gears to meet a growing demand from local newcomers and weekenders-turned-permanent residents seeking to re-imagine their remote-work environment or remodel their home.

If decades in the woodworking business has taught Ingersoll anything, it is how to pivot during a changing market and brace for the unexpected. Since he started woodworking in a one-room workshop back in the mid-70s, he has survived five recessions and two fires.

After serving as an infantry platoon leader in the Army’s First Air Cavalry during the Vietnam war, Ingersoll returned to Litchfield County in 1969 and needed a place to live. He built a house in West Cornwall, using old barn wood he salvaged from the area. “That house burned down, so I built another one”, says Ingersoll nonchalantly.

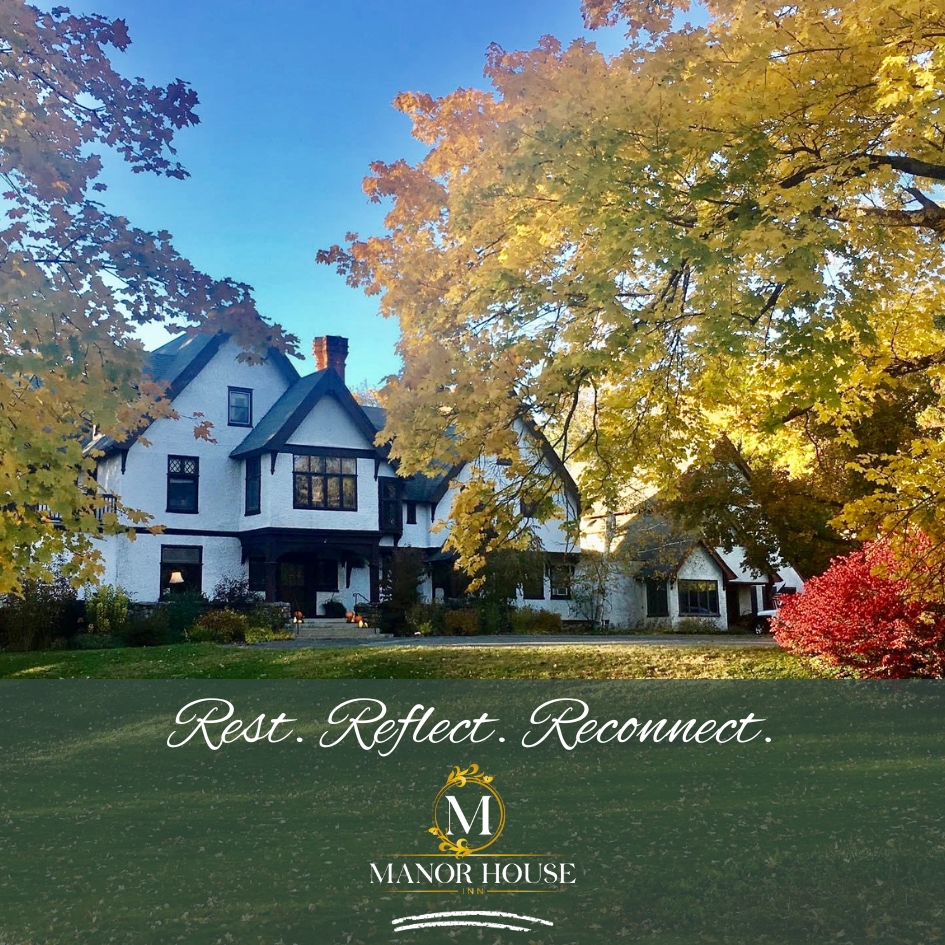

He is standing in his showroom in the historic Toll House building, which he compares to being in a harbor overlooking vintage sailing vessels. The Toll House, which sits opposite from the town’s famous covered bridge and just steps from the Housatonic River, is in the company of Victorian homes, weathered barns, and a train depot that, all of which once housed businesses that have come and gone—except for his.

Ingersoll began woodworking in the early 70s after friends in Manhattan asked him to redesign their apartment. For Ingersoll, it was an awakening. He realized furniture design would be his life’s work and he found his niche, drawing inspiration from Shaker furniture.

“I decided to replicate it to teach myself woodworking. I was aware of marketing cycles for furniture trends, and I thought I would be doing Shaker for like five years,” he says. “But Shaker became more recognizable in the antique and design worlds, and in1986, when Whitney Museum featured a Shaker furniture exhibit it catapulted internationally. I hired more craftsmen and began shipping furniture to Europe and Asia.”

Meanwhile, his designs kept evolving. “Five years ago, I realized about 85 percent of what we do is now contemporary furniture. We still do Shaker, country, and traditional pieces, but we also do five types of contemporary—modern, original designs,” he says.

His craftsmen, most of whom begin as apprentices, work out of a three-story building, where Ingersoll moved his operation after the shop attached to his showroom burned down in 1990. The business outgrew being in a small village long ago, but Ingersoll prefers working in West Cornwall, where he put down roots and raised a family. “We did a sort of straw poll among the workers and we decided we wanted to stay here. We’ve kept ourselves small, and maybe that is part of our survival skill,” he says.

It has always been Ingersoll’s desire to design furniture that advances the art form, although he explains that only two percent of the work he does is actually design. The rest is rebuilding and rebuilding, and perfecting the design.

The Shakers, in their effort to simplify their lives, took Chippendales and Queen Anne furniture popular in their time and redesigned those pieces, creating an entirely new art form.

“Eighty-five percent of a design is grounded in history, fifteen percent is a matter of intuition. In order to take an intelligent step forward you have to know everything that has come before,” he says.

Like the Shakers, Ingersoll has created a legacy in furniture design in West Cornwall. As for what the future holds, Ingersoll shrugs. “If this doesn’t last,” he says, “at least, I can say I’ve had a really good run.”